Plan for recovery when the heat passes. Brown patch on tall fescue rages on. Silent summer patch pathogen infection roars to life. Complicated leaf spot pathogens one of the stories of the season.

Weather

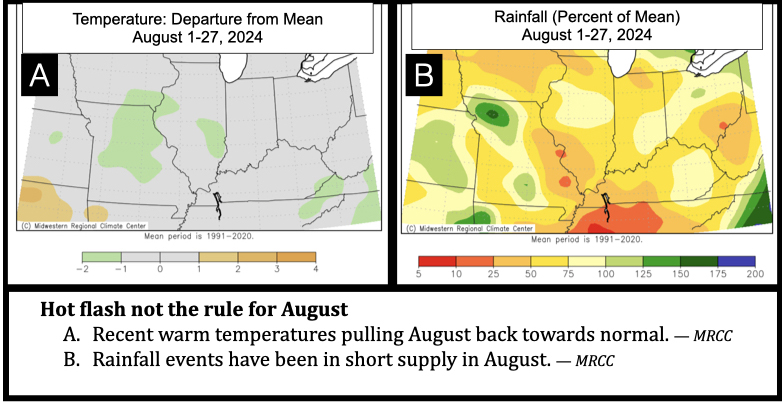

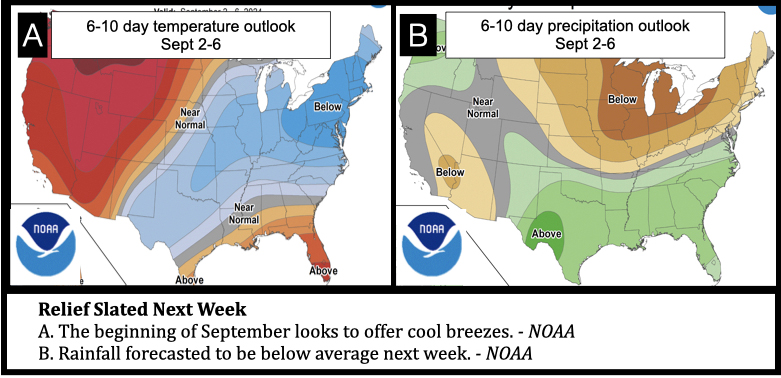

The last occurrence of seven days in a row of 90+ degree highs in Indianapolis was in July 2020, and if the forecast holds, this current span will duplicate this dubious feat. August is a crucial time for cool-season turfgrasses since they’ve run the marathon of heat stress in June and July and are at their weakest of the season. Fortunately, photoperiod (or daylength), is nearly two hours shorter now than it was in late June, so the overall length of the daily heat stress event is lower now than during the tempest of summer. In addition, this hot flash follows two five-day spans of below normal temperatures in mid-August which should have allowed some recovery. Therefore, despite this hot flash, the overall detrimental plant health effects of August temperaturehave been fairly standard. Humidity and rainfall have also been low for much of the month, reducing pressure from foliar diseases, particularly in mid-August. The return of tropical air with higher dewpoints has brought that pressure back, and several diseases have rebounded in the current conditions.

Forecasts indicate a nice break of relief and cooler temperatures to start September, along with a continuation of drier air and low rainfall chances. Next week’s conditions should again naturally pump the brakes on this stress/disease bump and provide a nice start to fall. For this reason, fungicide applications on lawns and other higher cut, lower amenity turfgrass areas may best be put on hold in favor of investment in cultural practices such as fertilization, aerification and overseeding. A hot take on this late summer flash of heat.

New Disease Guide for Lawns

A new extension publication is available at the Purdue Extension Education Store and on the Purdue turf website detailing the identification and control of the ten most common diseases found on cool-season lawns in Indiana and throughout the region. The article concentrates on disease management of tall fescue and Kentucky bluegrass and the critical differences in disease occurrence between the two species. The publication is currently free to download with print options available soon.

Brown patch ship keeps sailing

While brown patch on our creeping bentgrass surfaces faded away in mid-August, the disease on tall fescue stalled for a minute and then refired its engines quickly this past week. Tall fescue is a bunch type grass, so severe brown patch infections take longer to recover than spreading species. Despite this, tall fescue will survive most infections unless especially severe, but the long-term lack of density often results in weed encroachment. For this reason, fungicide applications for brown patch prevention or recovery are not suggested this late in the season. Instead, as noted above, place a focus on regaining density of affected areas with a fall overseeding program incorporating fertilizer and practices to ensure good seed to soil contact. In other words, the brown patch ship has sailed and now it’s time to bring your lawn back to shore.

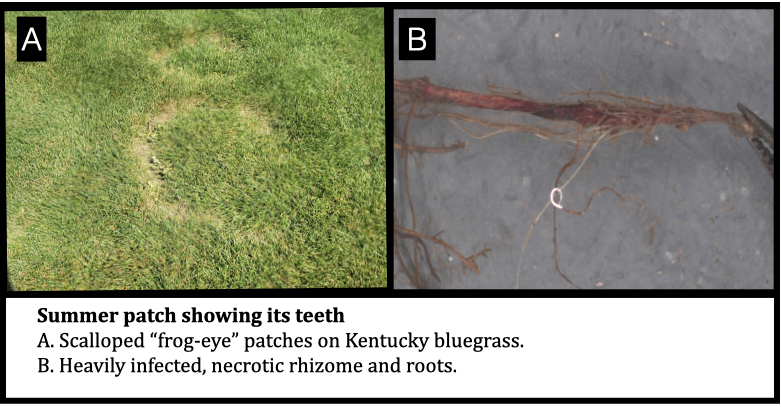

Summer patch on Drought Stressed Kentucky Bluegrass

A few samples of Kentucky bluegrass afflicted with the soilborne disease summer patch were submitted to the diagnostic lab over the past few weeks. Summer patch is especially difficult to control because the pathogen silently chomps on roots and rhizomes for weeks or months while aboveground the plant looks to be in fine shape. Late summer stress straws, which can be drought, high temperatures and/or compaction, breaks the back of the plant. Resulting symptoms occur in patches, (sometimes with distinct “frog eyes”), where the pathogen has impaired root function. The disease mostly affects the bluegrasses and may be the reason the shallow rooted weed Poa trivialis so conspicuously fails in the summer. Creeping bentgrass putting greens also can succumb to this disease.

On heavily infected Kentucky bluegrass lawns, the damage has been done and recovery should be encouraged. When temperatures moderate, consider applying ammonium sulfate as the main fertilizer source in September and October. Ammonium sulfate causes the rhizosphere to briefly turn acidic, disrupting the ability of the pathogen to further infect. Hollow tine aerification (not solid) can help alleviate compaction and also encourage recovery. Fungicides in the QoI class (e.g. azoxystrobin and pyraclostrobin) and the DMIs (e.g. propiconazole) are commonly used for prevention starting in late spring, but they must be effectively watered into the soil to be effective, a significant problem on non-irrigated lawns. Several summer patch resistant varieties of Kentucky bluegrass are available and should be considered when overseeding damaged areas this fall.

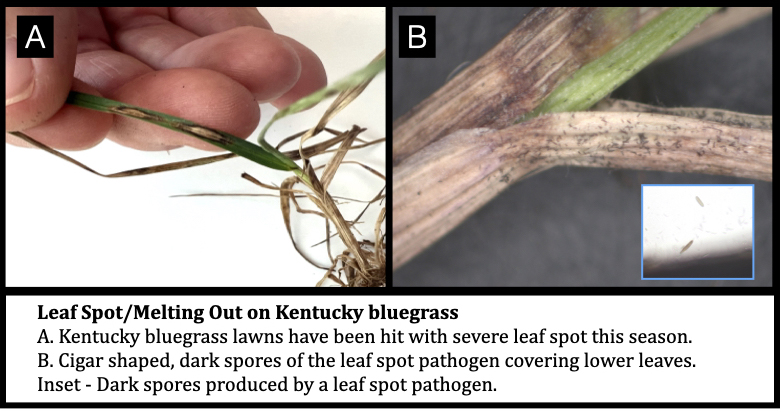

The Many Complications of Leaf Spot Diseases

Note: Gray leaf spot is a different disease than the leaf spot/melting out disease discussed in this section. To date, we have not yet observed gray leaf spot caused by Pyricularia oryzae affecting tall fescue or perennial ryegrass samples submitted to the diagnostic lab.

Leaf spot/melting out diseases on Kentucky bluegrass, fescues and especially perennial ryegrass have been a persistent issue through this whole season. A suite of different pathogen species in the Bipolaris, Exserohilium and Pyrenophoragenera (formerly the Helminthosporium group of species) have been implicated in causing these leaf spot diseases, and in many cases several can be observed at once in a single sample. The picture gets even more cloudy when other common pathogens such as Leptosphaerulina, Ascochyta, and Fusarium are also in the fold on untreated lawns. Further complicating matters, we are not discussing the different disease gray leaf spot (as noted above).

The growth habit of turfgrasses involves a natural rise of young leaves and senescence and death of older leaves, normally in a 30-60 day span. This habitat naturally fosters a suite of fungal saprophytes that can turn into an angry mob when environmental conditions are prime and/or turfgrass health is compromised. Unravelling which of these pathogen species are the true driver of the disease is difficult, since turfgrass decline may depend on several of them acting together as accomplices. Future research in this complex pathosystem is necessary.

In ground irrigation is a common denominator in many of these samples submitted from lawns. One homeowner commented that on May 1 of every year he sets his irrigation controller to water for 30 minutes three times a week and just forgets about it. Particularly this past spring, lawn irrigation was unnecessary due to persistent and oftentimes heavy rainfall. As a reminder, April in many areas had nearly twice normal rainfall and May an inch above normal. Analogous in the Indiana agronomy sector, 2024 will be remembered as the earliest and heaviest occurrence of tar spot, an important disease on corn. Most corn is non-irrigated and environmental conditions alone drove the epidemic. On lawns, overwatering further provided ample leaf wetness, high humidity and even better conditions for development of severe leaf spot epidemics that resulted in leaf blight and total plant collapse (melting out form of the disease).

Along with more prudent irrigation practices, renovating with improved disease resistant species or cultivars should be regarded as the sustainable, long-term option. If fungicide intervention is warranted, fungicides in the QoI class (e.g. azoxystrobin and pyraclostrobin) and SDHI class (e.g. fluxapyroxad and penthiopyrad) can provide good control.

Lee Miller

Extension Turfgrass Pathologist – Purdue University

Follow on Twitter: @purdueturfpath