In 2021, the entire Midwest experienced one the worst fall armyworm (Fig. 1A and B) outbreaks in decades, and for turfgrass professionals and enthusiasts it seems like we may be on the verge of another late-season outbreak. These seasonal, but sporadic insects started showing up at the end of August, and adults and egg masses are being reported across the region. The main difference between this year and 2021 is that movement of these insects into the Midwest in large numbers is occurring a little later than it did 3 years ago. Both the likelihood and severity of turf damage hinges on the short and mid-term forecast.

Cooler temperatures have likely slowed development over the last week, but the medium-range forecast is calling for warm, dry conditions over the next week meaning that development of fall armyworm eggs and caterpillars is likely to progress at a steady pace. The notable lack of rainfall in the forecast can set up conditions favorable for damage and slow recovery.

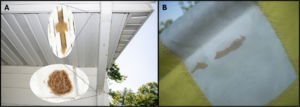

As their name implies, fall armyworms usually show up in the late summer and fall in this part of the country. These insects remain in subtropical climates for most of the year, but hurricanes, tropical storms, and weather fronts sweeping northward this time of year can carry enormous numbers of adults into the interior of the continent, sometimes raining fall armyworms over the entire Midwest and Northeast. Once they fall out of the sky, those adults lay eggs in masses on vertical objects including, signage, light posts, the sides of structures and even the flags marking golf holes (Fig. 2). When enough egg masses are laid in close proximity to one another, the resulting larvae (Fig. 3) can be so numerous that they eventually overwhelm surrounding turf, chewing it to the ground (Fig. 4).

Turf that was treated with Acelepryn for grub control during June or July is likely to be protected from fall armyworm assuming that applications were made at the higher end of the rate spectrum. Our data show at least 14 weeks of protection against fall armyworm at application rates 8.0 fl.oz./acre, and greater than 18 weeks of protection at 16 fl.oz./acre. You can do the math based on application timing. If you used imidacloprid or almost any other white grub insecticide for grub control, additional steps will be necessary to protect turf from fall armyworm.

Fortunately, these insects are relatively easy to manage and there are a number of insecticide active ingredients that will keep them in check (Table 1). Liquid applications are almost always preferable to granules since liquids provide better coverage and work more quickly. However, granular formulations will work as long as they are followed immediately with rainfall or irrigation to release the active ingredient. Mowing just prior to application can increase penetration of the insecticide through the canopy and into the spaces where fall armyworms are active and feeding. No post-application irrigation is necessary for liquid applications and these applications should be left in place for at least 24 hours before irrigating.

If damage does occur, giving turfgrass the best opportunity to recover should be a top priority. While soil temperatures remain high, disturbing plant crowns should be avoided, so raking out dead material, core cultivating and slit seeding should be put on hold if possible. Instead, consider irrigating the turf if the soil is dry. Irrigation can help reduce soil temperatures and stimulate plant re-growth. If the turf is not fertilized, a very light fertilization (<0.5 lbs. of N per 1000 ft2) may be in order, but keep in mind that well-maintained turf will generally not require additional nitrogen. If the turf isn’t growing, don’t mow it. In other words, do everything you can to protect the plant crowns as these will produce the new tillers and leaves that mark recovery.

Given the late starting date of this outbreak, we are unlikely to see another generation of fall armyworm larvae, but turf mangers in the southernmost areas of the state should be vigilant through early October. That means scouting for egg clusters and soap flushing for larvae are the best ways to identify potential infestations before they cause serious damage. If we get lucky, temperatures will moderate and put the brakes on fall armyworm development, but weather will be the key. The last half of September and first half of October could be interesting.

Focus on detection, prevention and turfgrass recovery and regrowth, and be alert to egg masses and developing larval infestations. If another generation of fall armyworms unfolds, its potential impact on turfgrass winter-hardiness and spring green-up could be a significant concern.

Doug Richmond

Professor and Turfgrass Entomology Extension Specialist

Purdue University

| Figure 1. | Figure 2. |

a) fall armyworm caterpillar with characteristic stripes and inverted, light-colored Y-shape on the head (John Obermeyer Photo). b) fall armyworm adult (Nate Fair Photo) |

a) A mass of fall armyworm eggs deposited on a) the side of a house (John Obermeyer Photo) and b) a golf flag (Cale Bigelow Photo) |

| Figure 3. | Figure 4. |

A group of newly hatched (neonate) fall armyworm larvae hatching from a cluster of eggs. |

A stand of turfgrass damaged by fall armyworm larvae at the end of August in West Lafayette, IN 2021 (Jim Scott Photo). |

Table 1. Insecticide active ingredients registered for use against fall armyworms in turfgrass.

*Always consult label directions for specific timing and application recommendations.

aFor use on golf courses and commercial sod farms only.